Shelving and safety: an overview

-

By Guy Robertson

Assessing, evaluating, maintaining, and selecting shelving from the view of a disaster planning consultant.

This article was originally published in FELICITER a publication of the Canadian Library Association, Volume 42, Number 2 ISSN 00149802, February 1996, pp. 33-36 and is reprinted here with permission.

Shelving is fundamental to our culture. It is likely that prehistoric cave-dwellers stored their tools on any convenient stone shelf., millennia later, large shelving systems holding everything from clay tablets and papyri to pottery, grain and weapons became common in the temples and warehouses of the early cities. Nowadays almost everything we eat, wear and read has spent time on a shelf, and many of the materials used to build our residences, offices and cars were stacked on shelves before they were hammered, welded, bolted or screwed into place. Since shelving is such a basic physical object, so common and apparently uncomplicated, librarians often take it for granted. We can work around miles of shelving for decades without paying much attention to it. It seems as solid and dull and immovable as the concrete in the foundations of our buildings. In an age of increasing budgetary cutbacks, however, when library facilities might not receive the same level of maintenance as before, shelving deserves more consideration. Like everything else, it ages. Without proper inspections and repairs, our shelving can become dangerously unstable. For the sake of safety, we need a stronger awareness of the shelving we work around.

|

Since World War II, libraries have purchased shelving of all kinds from a growing number of manufacturers. A survey of the shelving systems in Canadian libraries would reveal many different brands of shelving installed in myriad ways. Think of the huge metal ranges in university and college stacks that become what a British engineer calls catacombs of literate behaviour'. Many university stacks were installed in the 1950s and 1960s as post-secondary institutions expanded to meet the needs of the Baby Boomers. Some of these stacks were constructed from metal that manufacturers acquired as military scrap. It is possible and wonderfully ironic that the university shelf holding a strong collection of works on Buddhism once formed the bridge of a destroyer or the turret of a six-inch gun. Libraries are the fruits of peace: we have beaten our swords into ploughshares and our navy into free-standing bracket shelving.

|

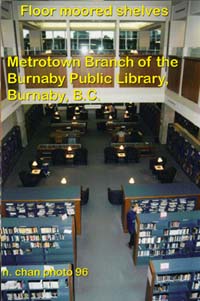

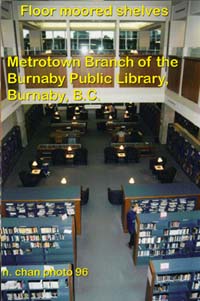

Canadian public libraries contain the broadest variety of shelving. Newer public libraries have shelving systems, designed by teams of librarians and architects to provide convenient access to collections. As in any location where the weight of furnishings is heavy, floor loading is a constant concern. Library planners insist that the combined weight of all shelving and furniture should not exceed 150 pounds per square foot, and this figure can be easily respected when planners can determine exactly what will be installed or positioned in a particular space. Over time, however, librarians might modify a system to meet new needs. For example, in a large public library, several old ranges were removed from their original location to accommodate an expanding children's division. The old ranges came to rest in a storage area on a different floor. In light of the size of the public library and its inventory of furnishings, such a change might seem negligible. But the floor loading in its storage area has increased, and while floor collapse is unlikely, there is a chance that the floor will shift and cause a shelf collapse.

We refer to the configuration of our shelves as a system. This designation is accurate as long as the configuration is developed as a single entity for specific purposes and in response to the library's physical conditions and limitations. When we alter the system, move things to different locations, revise and reinstall, our system begins to lose its integrity. It becomes a collage. This is not necessarily a bad thing; many shelving collages serve patrons better than the original system. But reinstalling shelving introduces new stresses on bases, brackets and braces. Wear-and-tear can accelerate. Consider how rickety many shelves become after we move them.

Since special librarians acquire many of their furnishings from various sources throughout their host institutions, special libraries are more likely to contain shelving collapse. An extraordinary example is an engineering library in Vancouver, B.C. The technical reference collection is housed in standard particle board units moored to the wall. The circulating book stock is kept in ranges of heavily-braced commercial shelving that could support the weight of the entire collection, case shelving that once held a collection of fossils from the Burgess Shale, and old bracket shelving that might have been to sea in another incarnation. Beside the librarian's desk is the ready reference collection - phone books, dictionaries, AACR2 and a restaurant guide - housed in the shelving of a 'home entertainment centre 'from the 197Os: this contains separate compartments for your television, bar, sound system and Bee Gees albums.

Such a collapse does not seem stable, but the engineers who use the collection inspect the shelving regularly to make sure that it

poses no risk. The librarian reports any sign of wear-and-tear, any squeak, groan, or list. Repairs are quick. A shelving unit can be re-moored, adjusted, re-bracketed, or simply replaced in a couple of days. This non-system is not ideal, but it does its job inexpensively, efficiently and safely.

A shelving risk analysis begins with an inventory of all shelving on the library site. This inventory should include:

- The number of self-contained shelving units in different departments. A self-contained unit can stand on its own without support from another structure.

-

The kinds of shelving on the site. This section includes a description of the shelves in all public and workroom areas, as well as the old storage collage in the basement, and the wall-mounted shelves for cleaning supplies in the janitor's closet. Revolving cases, book trucks, compact shelving, file cabinets, and shelves mounted in workstations should be noted.

-

A brief description of how each unit is moored to the wall, floor, or other units.

-

The estimated weight per square foot of shelving on different floors.

-

The estimated age of all units.

-

All floor plans, from the original configuration to the current layout. These plans often contain valuable information on floor loading, vendors, and ages of units.

-

Any risk history. Has there ever been a shelf collapse in the library?. Has any staff member or patron ever been injured by a shelf'.? Is there any place in the vicinity of a shelving unit where injuries have occurred in the past?

The inventory leads into a shelving inspection record, which includes the following sections:

- A description of wear-and tear and any components that could cause injuries. Note parts that are loose or missing, any listing or change of shape, rust spots, sharp edges, and any mooring that has weakened over time. One useful test for long ranges of shelving is the 'one-hander': if you can cause a range to undulate by pressing against an end-panel, then it is probably not safely moored.

- Janitor's shelving.

- Is it securely mounted? Does it hold potentially dangerous chemicals, such as ammonia? If so, are the containers securely stored? Is there a lip along the edge of the shelf to prevent containers from falling off.

- Revolving cases.

Have they been spun too many times by small children waiting for browsing parents? Does any case seem inclined to tip? When you turn a revolving case, listen to it. Does it sound as if one of its parts is rubbing against another? Ideally, you will be able to inspect your revolving cases when they are fully loaded, since greater weight reveals weaknesses faster than a light load.

- Book trucks.

Are they inclined to tip as you turn a corner? Are the wheels loose or worn out? Does any truck feel unstable when fully loaded?

- Compact shelving.

Does it run smoothly along its tracks? If your compact shelving system comprises electricity to provide power for movement and monitoring, is the wiring in good condition? Does the shelving squeak or rattle as it moves? Has the vendor or physical plant manager inspected your compact shelving lately? Compact shelving is rumoured to be a greater risk to users, but media reports do not confirm that well maintained compact shelving is any riskier than other kinds of library shelving. In fact, state-of the-art compact shelving can be much safer than other systems that are unmoored or cheaply constructed. Nevertheless, since compact shelving comprises moving parts and, in the more sophisticated systems, electronic circuitry, it must be inspected and maintained more often than other systems.

- File cabinets. Are they securely moored to the floor or wall? Are the drawers easy to open?

- Workstation shelves. Are these overloaded with software manuals and unmoored printers? Are they strongly moored to their supporting components?

Other risk factors that you should note during your inspection are:

|

|

-

A common risk that is not life-threatening is moisture, which seeps into walls and can deteriorate wall moorings. Libraries located in regions that regularly experience heavy rainfall should note any sign of leaks or seepage, such as stains on the floor or walls. Fortunately, moisture is much slower to loosen furniture than an earthquake; nevertheless, its cumulative effect over several years should not be ignored.

- Type of library. Shelving risk increases with the number of patrons and staff members who spend time in and around shelving. Busy libraries will inevitably experience more wear-and-tear to all furnishings and fixtures than special libraries with limited access.

- The library building. Older buildings are more likely to have suffered more structural damage over the years, and records of this damage might have disappeared. Thus, an older building, such as a Carnegie library, might have less stable flooring and foundations. Walls in these libraries might not be able to provide effective mooring.

While each building must be considered on its own merits, newer buildings constructed according to the specifications of the current National Building Code are less likely to experience shelving safety problems, especially if shelving systems are an integral part of the building's design.

- Aisle widths. Generally, the wider the aisles, the less risk there is from shelves. Library administrators are determined to use their shelving space as cost-effectively as possible, but shelves situated too closely together can result in more wear-and-tear to shelves and collections as book trucks bump their way along narrow aisles. Narrow aisles also encourage staff members and patrons to bend and twist themselves in such a way that back injuries can ensue.

A comprehensive risk analysis should include suggestions for risk mitigation. Often, mitigation measures to reduce shelving risk are too expensive to take in the immediate future. In such instances, a phased mitigation plan is recommended. It is wise to deal with the most unstable shelving first. If it cannot be repaired or made more secure, it should be replaced. Those unstable units closest to public and staff areas should be repaired or replaced first. Note that in many libraries, the riskiest shelving is in the reference area. The reference shelves hold greater weights than other shelving units, and they are in constant use by staff and patrons. Frequently, a set of the heaviest reference shelves stands directly behind the reference desk. If these shelves are deemed unsafe, they should be repaired or replaced as soon as possible.

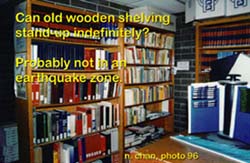

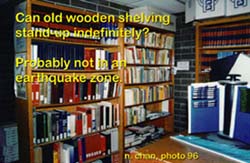

Are shelf collapses common? It is impossible to judge from media reports. What is important in such reports is not what is discussed, but what is left out. In fact, it is rare to hear the reasons for a shelf collapse, especially if somebody has been injured or killed in the event. But certain circumstances usually prevail: the shelving that has collapsed is older, heavily loaded, and not well moored, the victim has worked around the shelving for years, the victim was working alone at the time of the collapse, and did not receive prompt help.

Most shelf collapses, however, are not fatal. In this writer's experience, they occur in basement and back-room storage areas, frequently during off-hours. The shelving is either old wood or even older metal, and the flooring in the immediate vicinity appears uneven. A risk analysis would have easily confirmed the instability of the shelving before it collapsed, but storage shelving is not considered a high priority. Unfortunately, as budgets shrink, safety for entire libraries is becoming a less outstanding issue to administrators, who must rationalize every small expense. We trust that they will reconsider their priorities before gravity strikes a blow in a crowded public area.

Guy Robertson is acting chair of the Library Technician Department at Langara College and a disaster planning consultant at Proact DataStor Corp. in Vancouver, B.C. Photographer Neal Chan is an information specialist in Vancouver, B.C.

|

[ Feature Articles

| www.provenance.ca home page

| Top of Page ]

Publisher publisher@provenance.ca © 1996 -- Corporate Sponsor - Internet Gateway Corp.

Moved to Provenance.ca from NetPac.com/provenance April 25, 2002 - Contents last update July 2, 1996

|